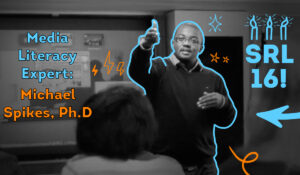

SRL 16: “Producing media helps young people make sense of the world” and more from media literacy expert Michael Spikes

Celebrating 16 years of Student Reporting Labs!

Celebrating 16 years of Student Reporting Labs!

PBS News Student Reporting Labs was founded by Leah Clapman in 2009. What started with six pilot schools reporting video stories in their communities has grown to service hundreds of schools and thousands of educators and students across the country. To commemorate our “Sweet Sixteen,” we spoke with five of the original pilot educators and journalists who helped prove the concept and build the foundation of this vibrant community of storytellers.

An expert of the field of media literacy education, Michael Spikes has taught journalism and production for over 15 years. Today, he is a lecturer at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism and the director of Teach for Chicago Journalism, a program that supports scholastic journalism programs and local journalists. Spikes contributed to some of the first Student Reporting Labs curriculum while teaching production classes in D.C. public schools, and his classroom was one of the first SRL pilot sites in 2009.

In this Q&A, Michael Spikes offers an expert’s take on the mounting struggle to access quality information, and advice for teaching others to be quality-minded consumers.

This Q&A has been lightly edited for clarity.

What impact did media education and SRL have on your students back in 2009?

I started in a charter school in 2005. At that time, the No Child Left Behind Act was playing a big role in school policy. Many of our students struggled with basic reading skills, basic writing skills, things like that. One of the things that we were able to do in that program was give students an opportunity to engage with current events in ways that they didn’t traditionally. They might’ve read the free, tabloid size papers at train stations, but they didn’t regularly engage with the news and current events.

I had a few students who found that taking these kinds of classes really engaged them in production skills. I don’t want to overstate it, but it definitely helped some students re-engage with schooling in total.

Why is it important that students engage with journalism not just as consumers, but as producers?

I think at the core it’s about learning what it means to be engaged within a community. Because of the loss of local news in so many areas, a lot of young people are losing that ability to connect to their communities through local news. And while yes, we have access to tools like social media, algorithms aren’t always locally focused, nor are they focused on giving young people information that is reliably credible. That has served to fracture communities and not be really helpful to young people. Young people in these very formative times are getting lots of different kinds of messages that are not always true to their local context.

Producing media helps young people make sense of the world and understand the role media plays in understanding one another, how media influences portrayals of different groups of people, and influences our constructions of reality. When you put students in the role of being media producers – and the Student Reporting Labs definitely does this – it gives them a framework for more thoughtful media consumption and production, so that they better understand their roles as not only producers, but also as media consumers.

What did you enjoy about working directly with students in the classroom?

I learned a lot. I never went through any kind of formal teacher teacher training. I did an associates in basically audio engineering – like I learned how to mix albums.

I taught in the DC public schools, and the school I taught in was a challenging school to be in. When somebody says “inner city school,” we were like the poster child for that. You had students that sometimes came. The joke that we teachers would sometimes tell each other is we would be like, “The weather nice? They not coming. Is it raining? They not coming. Is it cold? They not coming. Is it hot? They not coming.” We would deal with all kinds of things in the classroom, but it was one of the best places for me to learn how to teach. I had to be adaptable. The lessons I learned in those classrooms directed the work I’ve done going forward.

I’m in a position now where I speak to college students on a regular basis. At a place like Northwestern, I’m talking to a much different group than who I taught in high schools. But I learned how to make sure that I connected with my students to find out what kind of things they wanted to learn, to make sure that not only were they meeting my expectations but that I met theirs. That was and is my number one priority. As I go back through my career I just really feel really fortunate to have found ways to combine my two passions: technology and media, and sharing information with others.

What are some of the obstacles that you’ve identified to getting young people interested in local news? What advice would you give teachers who are having trouble engaging their students?

Young people are at a stage in their lives where they’ve moved from their household context being the end all be all. They’re thinking about themselves and their peers more. Something that worked well to engage my students in issues around news literacy was to find stories that connected with their own personal identities. When we see stories of people who are like us – who share our interests, personal identities, backgrounds – those things can bring us into a story.

It also helps to really focus on the storytelling aspect. Young people get so many bad examples of storytelling. Show them really good stories. You can always engage somebody with a good story, and news can do that really well.

I taught students who really couldn’t care less about news. There was this really old story from the CBS evening news about an autistic student who was the ball boy for the basketball team, and during one of their championship games a player got injured. The autistic student was subbed in, and he just kept sinking all these three-pointers throughout the game. That story really caught the students’ attention, they really connected with it. That was an example of a really great, locally focused story you can build lessons around.

Everybody has a story to tell, right? It’s up to you as the teacher to help students find theirs.

What are some common barriers to understanding and developing media literacy?

My introductory lesson is all about making distinctions between different genres of media. Today there are so many people that self-label as “news”, but they don’t follow journalistic practices. The lesson that I always draw on tries to make distinctions between how journalism is different from all this other stuff.

More young people are becoming more critical about what they’re seeing, but it depends on the context. Many more people nowadays, if you say to them the phrase “media literacy,” they go, “Oh, yeah, that’s really important!” But what has not changed is that people still think, “Well, I have it, but other people don’t.” Everyone thinks that the problem is with everybody else. So that still has to change.

Why do you think it’s important that public media continues to exist?

As a consumer of information, PBS, NPR, public media broadly is my go-to. It is the place that I put the most trust in, because I hold it to high standards and it consistently meets those high standards.

I teach people about how to find credible information, so I’m always looking for in-depth, original reporting that deeply considers the multiple contexts that are happening in any situation. These days so much of our information about current events comes in the form of a headline, a hot take, some random person just talking about it, right? But I can get the headline from anybody. I want a trained individual that is working with a team of other people who are creating media with the express intention to inform and give me insights. I want my news to be insightful. The phone goes off ten times a day to tell you what’s going on, but really if you really want to understand what’s happening, you need sources that take the time to explain.

One of the things that happens in our increasingly fractured media ecosystem is that people assign little to no value to information because it’s everywhere. That makes it much harder for institutions like public media who are thoughtful in the work that they do. They’re intentional, and the intention is not to persuade you to think some way or get you to buy something. It’s to help you unravel what’s going on. With that being the case, it sickens me to see what’s happening. The way that this administration approaches information that doesn’t align with their own worldviews, and just dismisses it and calls it biased. Observable, verified, factual information. It really makes me worry about the future. I find public media crucial and all the more important in our current era.